U.S. Cities: shifting

mobility patterns

Given the COVID-19 moment in which this book was published, we understand the amplified importance of such interrogations at the brink of a turning point; an upheaval of the status quo. We realize that the long-run effects that this moment of disruption may produce in the American mobility landscape are cloaked in uncertainty. Yet, it is precisely because of this uncertainty that the findings within the pages of this publication are so valuable, because they offer a snapshot of some of the defining directions and travel characteristics preceding the major disruption. Beyond results, this book’s contribution also lies in its methodology and approach following cities with progressive traits as trendsetters for the country’s future. Ultimately, the book offers an evidence-driven narrative for future mobility based on a collection of timely data.

Tracing mobility through a multi-focal data lens

Multi-dimensional city growth index

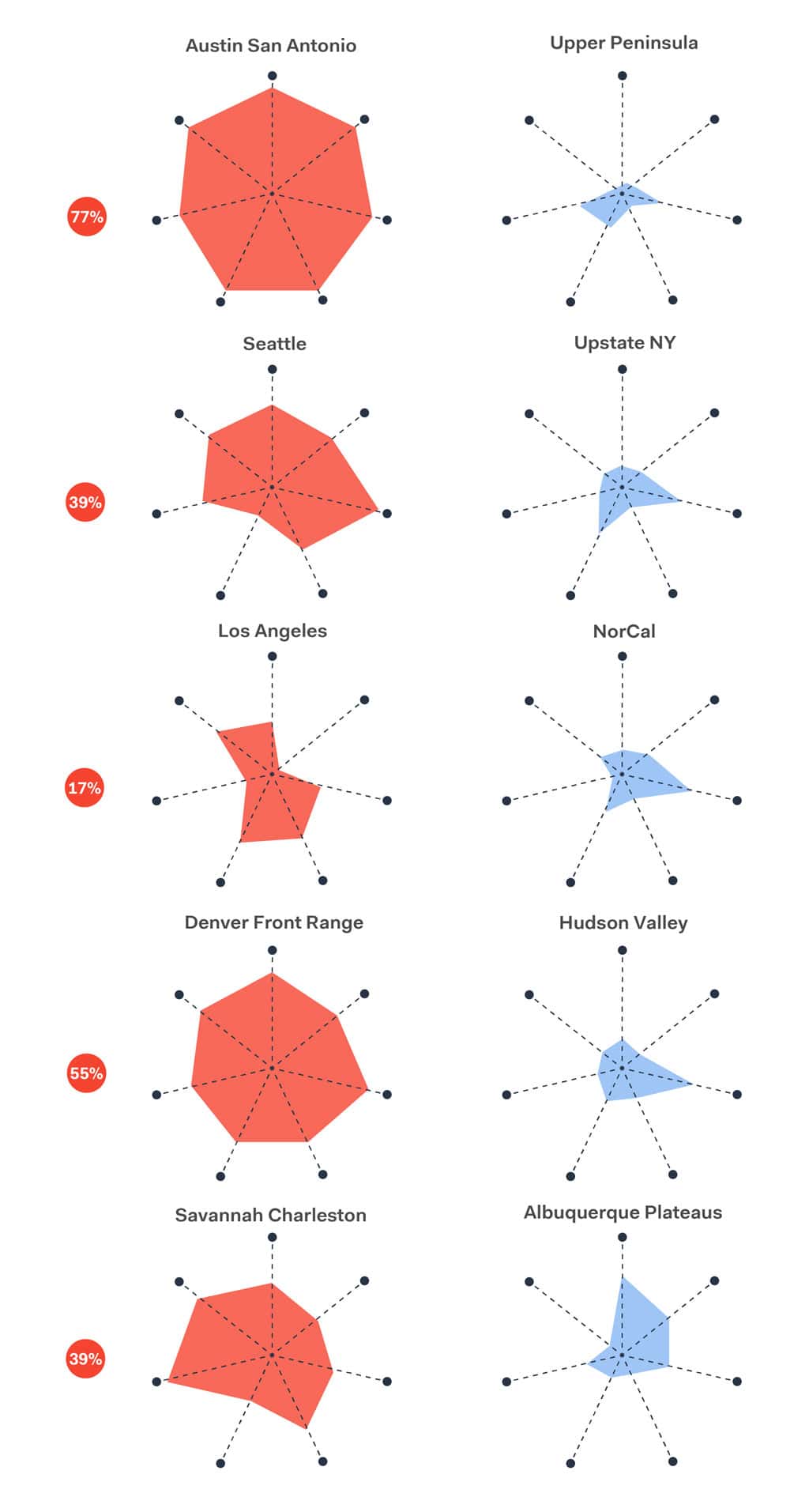

Diverse city profiles on the growth spectrum

Tracking emerging mobility trends –

Are there new mobility directions?

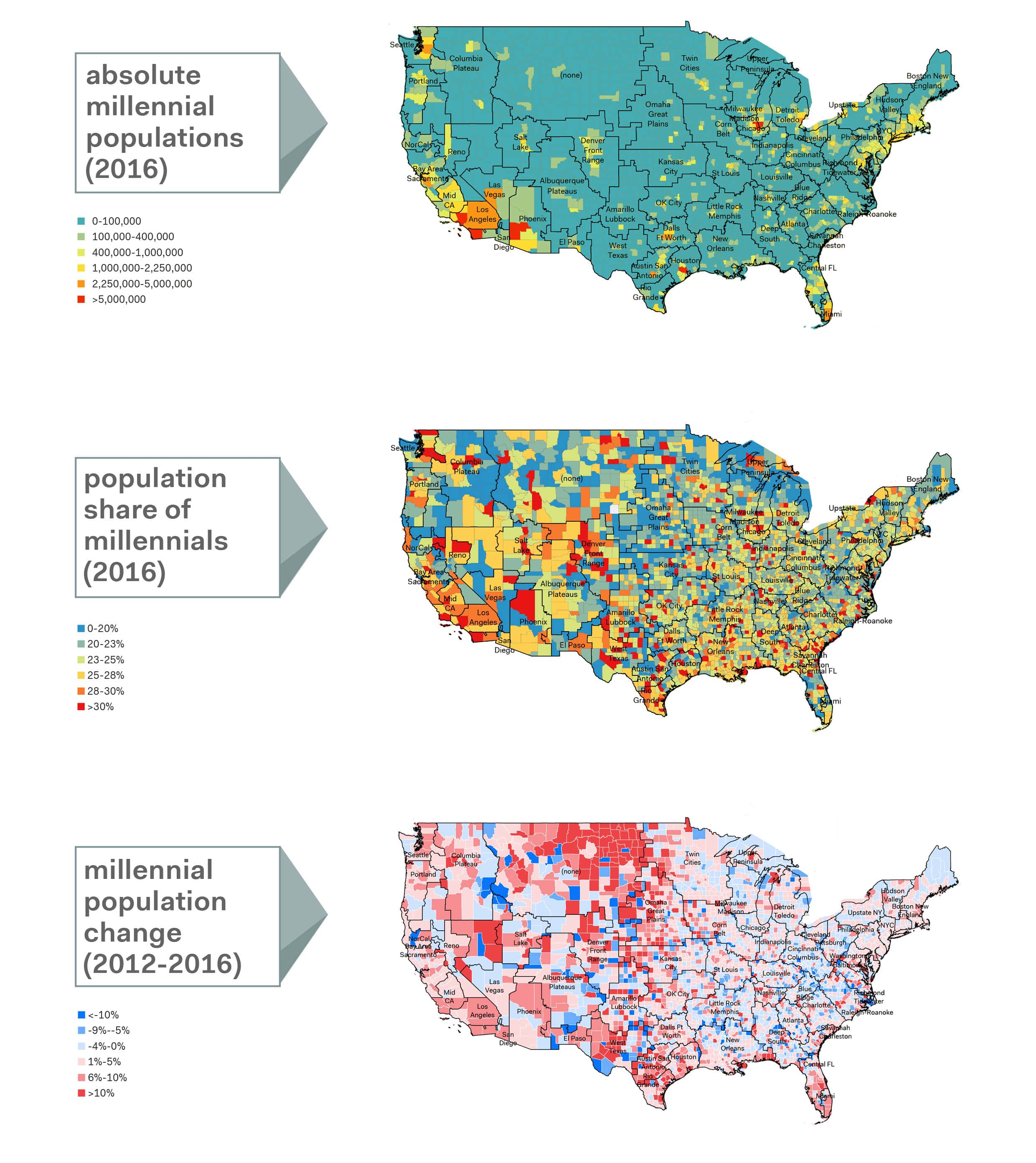

Strength in numbers: where are millennial populations growing?

Data clearly shows population surges in America’s Rocky Mountains and Southwest regions

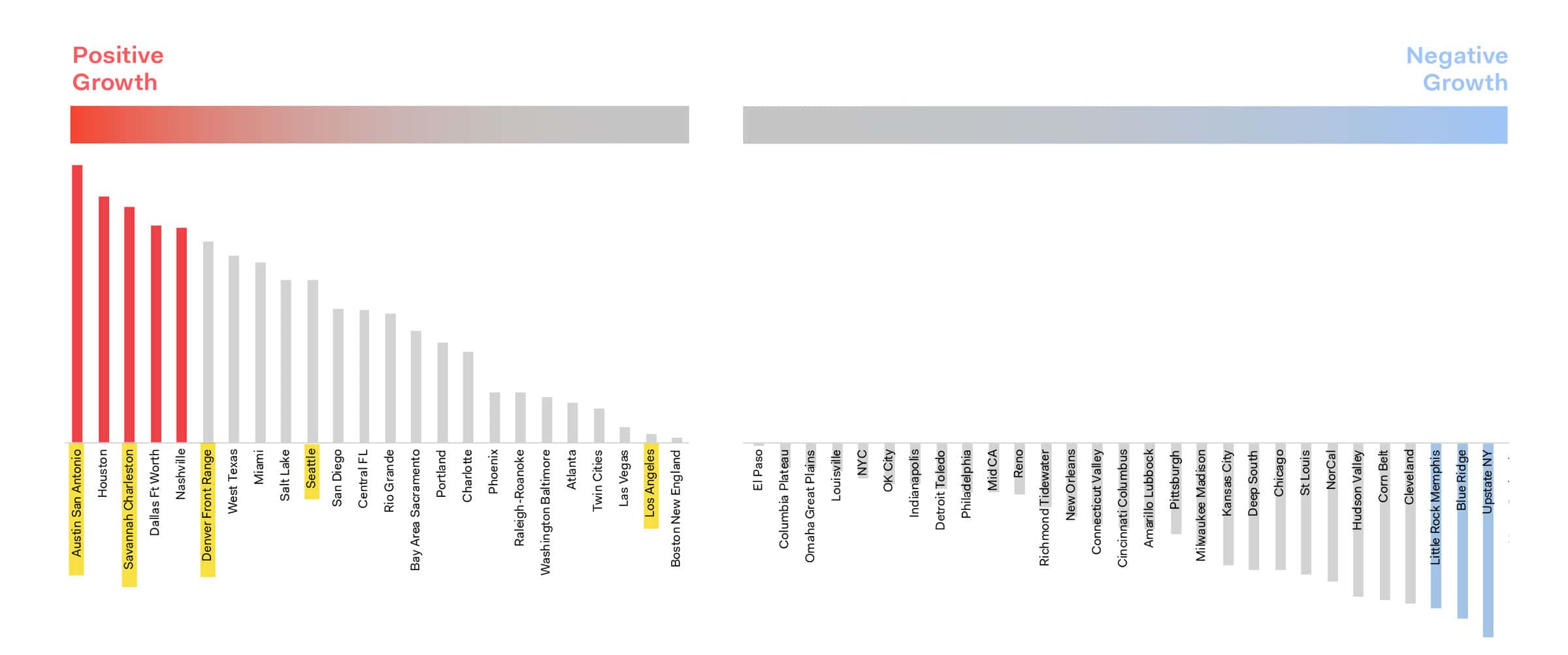

In this study, the geography of the United States is segmented into 55 megaregions, redefining regions as areas with commuting and economic relations. The megaregional map is based on a superimposition of visual and logarithmic computations of megaregions; ensuring it is grounded in empirical analysis but refined using interpretive cartographic methods.

A general reading of the millennial population (defined at the time of the study as those falling between the ages of 25-44) in the United States in absolute numbers based on 2016 census data highlights higher concentrations in the coastal regions. This trend is in keeping with general population figures. According to the United States Census Bureau, about 30 per cent of the population lived in counties directly on shorelines by 2017; a 15 per cent increase since 2000.

Popular studies and readings on the habits of millennials tend to suggest a clear demarcation from previous generations, and particularly in the United States. Among other things, it is suggested that they are more transit-oriented, less car-oriented and more open to alternative forms of mobility than their predecessors. Looking at the shares of millennials relative to total populations across the country, we find that this share is generally above 20% in most regions today. Comparing this data with the situation just 4 years prior, we find that millennial shares rose in most regions across the United States, with profound increases particularly in parts of central and western America, where increases are recorded at 10% and above. The highest increases in millennial populations are all concentrated in the state of Texas, where three of the five most attractive cities for millennials are located (as previously shown in Chapter Two).

What do these demographic changes mean for American mobility trends? The following section studies a number of mobility trends in cities of diverse demographic and economic patterns as a way of investigating emerging mobility cultures. By interpreting data from the most recent census figures, we explore whether these surges in millennial populations are accompanied by any mobility shifts in America’s urban areas.

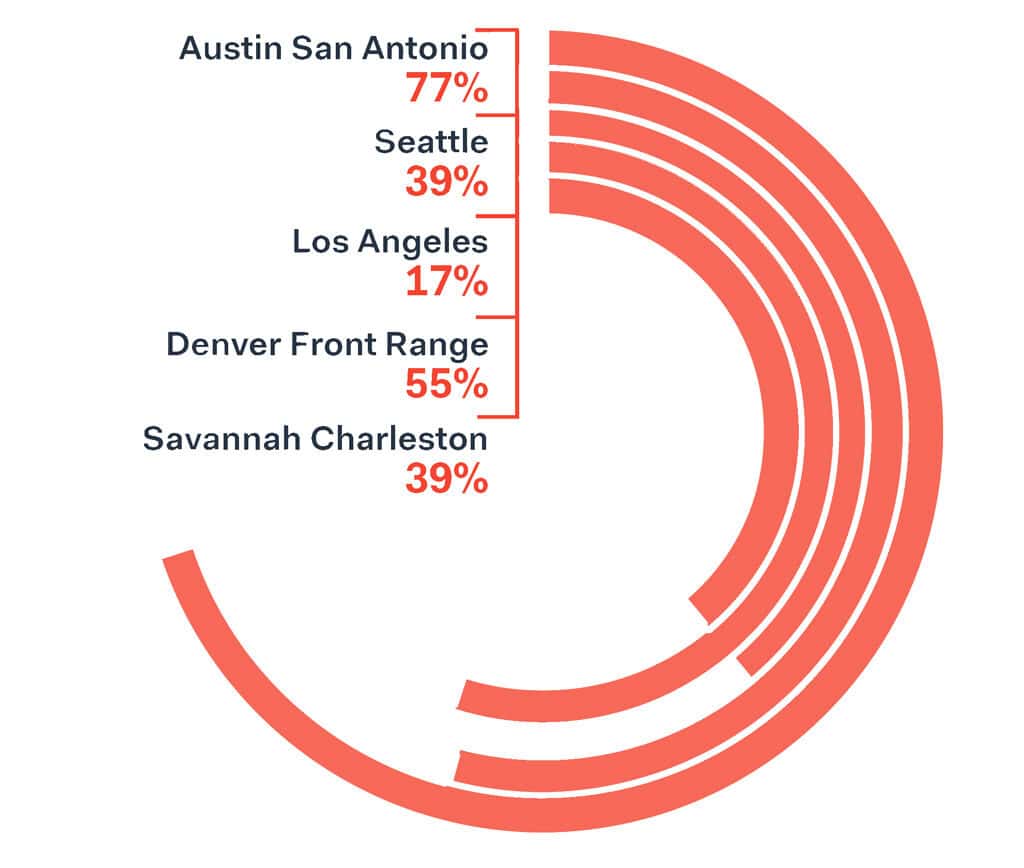

Diverse city profiles on the growth spectrum

Millennials are in fact increasing in central areas of all five cities under study and decreasing from some surrounding districts. Save Austin, the same trend cannot be traced for the Over-65 population, which in the short four-year span has tended to increase in suburban areas. In Savannah, a cluster of increases is recorded in the area just northeast of the downtown area.

Sharing mobility: a differential upsurge

Diverse growth trends as new mobility options set their course

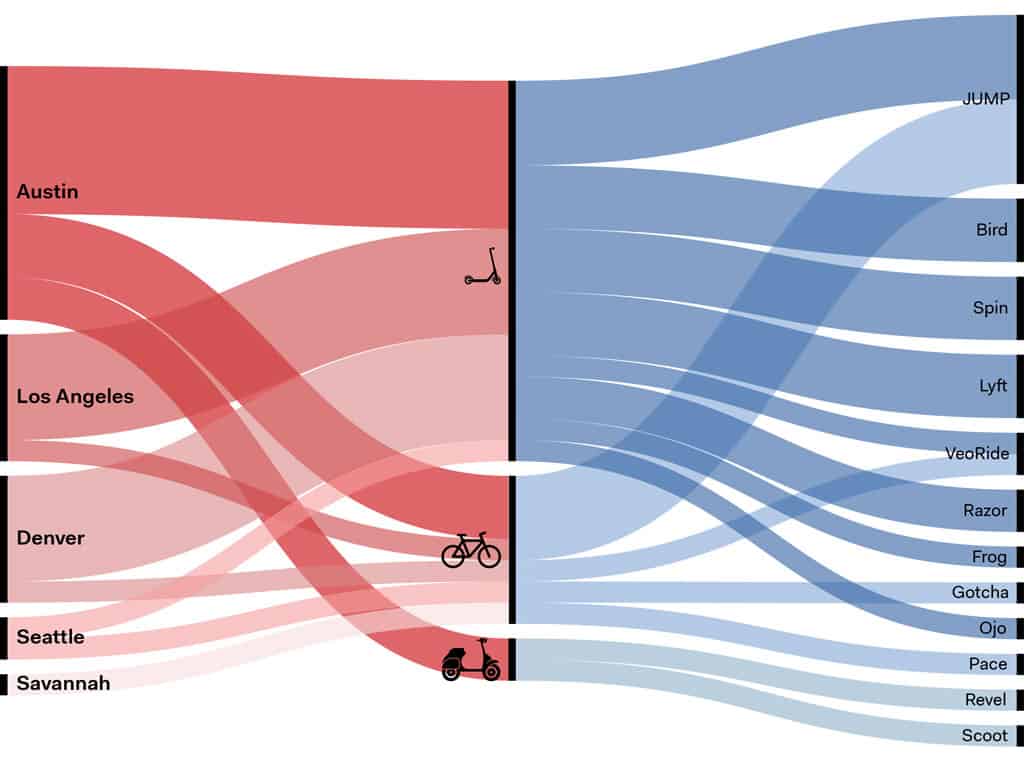

From carsharing to bikesharing and scootersharing, much has progressed in the U.S. mobility landscape in the past decade or so. New shared mobility services have been exponentially growing in the past years, with various trends across the country. As the opposite maps show, bikeshare systems, which have been growing since 2010, today range from less than 1000 bikes in some cities to 10,000 bikes in others. Scootersharing, in retrospect, has only been around since 2017. Yet, a number of cities have rapidly surpassed the 10,000 scooter mark. Likewise, the carsharing market has seen a continuous upward trend in the decade 2006-2016, growing by 15 times the number of registered members across North America in 10 years (as shown below).

This diverse uptake of shared mobility services is evident in the cities under study. Taking bikeshare as an example, we find that Denver’s B Cycle system is ahead of the race, dating back to 2010. Los Angeles’ Metro bikeshare system on the other hand has only been around since 2015. Even newer, Seattle’s bikeshare system, which as of 2019 is composed of two private providers (JUMP and Lime) and is only just beginning to find ground after failed pilot attempts in 2015/2016.

The selected cities vary in their offerings of shared mobility services. Bikeshare trends are one example: while Denver’s B Cycle system has been around since 2010, Seattle’s bikeshare program only began in 2016 and companies are still changing year on year.

Micromobility services available in selected cities by type and provider. Data source: NUMO (New Urban Mobility Alliance)

Telecommuting on the rise

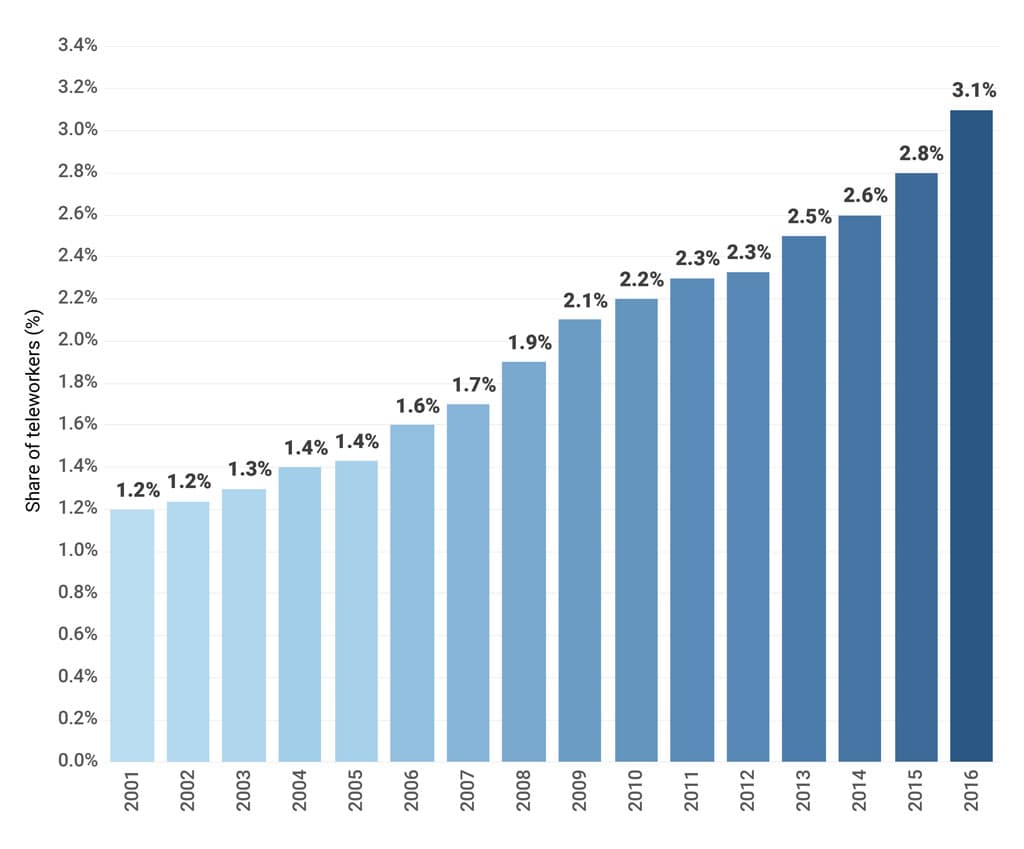

Prior to the large-scale adoption of home working across the U.S. during the 2020 pandemic situation, a clear rise in telework popularity was already in motion. Between 2001 and 2016, the share of full-time teleworkers more than doubled in the U.S., suggesting that it was already gaining popularity before there was a direct need for it.

Share of full-time teleworkers in the US, 2001 to 2016. Data source: American Community Survey

Share of full-time teleworkers in the US, 2001 to 2016. Data source: American Community Survey

The big takeaways

Cross-city analysis: trip data under the microscope

Setting the scene

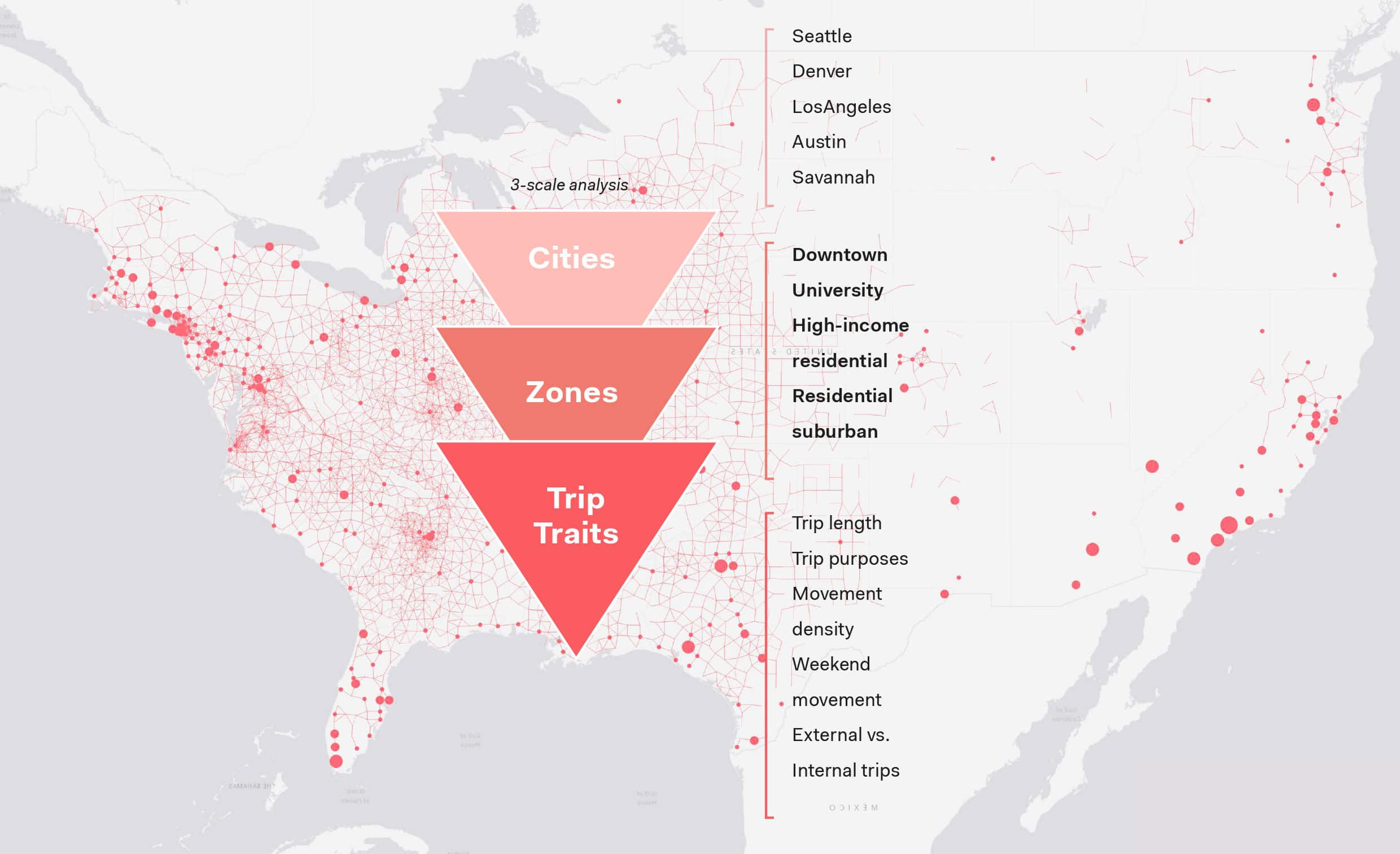

For a cross-study benefit the same classified zones were identified for each city. These zones are: downtown, university area, high-income residential and suburban residential zones. In continuity with previous chapters, these zone typologies were chosen to reflect contrasting profiles for socio-economic traits that have been identified as criteria for emerging mobility trends. Such traits include millennial population, millennial population growth, active modal shares, etc.

Trip trait 1: Trip Lengths, who’s counting? — What makes us most likely to spend more time moving around?

Trip trait 2: From-To — A purpose-driven trip analysis

Trip trait 3: The density dance — how are movements distributed within our cities?

Trip trait 4: The Sunday/Monday divide — what are we doing differently on the weekend?

Trip trait 5: Trans-locale — the where and when of moving between zones versus moving within them

Concluding remarks

In some instances, there are differentiated trends even between twin zones. Movement density is one such diversified trait: high-income residential areas have the lowest overall movement density of all areas and suburban residential areas have three times that density. A similar distinction can also be made between densities of the twin group on the higher end of the scale: on average, downtown generates 3 times the average movement of university zones. In any case, the performance of downtown areas is more closely linked to the morphological structure of the city, as discussed earlier in the role of mono- and poly-centricity.

In other studies, distinction between downtown and university zone performance lends itself more to scheduling factors relating to the main function of each area. For example, internal movement in university zones are amplified more broadly over the morning and afternoon period, whereas in downtown areas the rise is more restricted to the short two/three-hour segment corresponding to office lunch breaks.

Considering the fact that movement density multiplies by large factors in downtown areas relative to other zones, it becomes clear that a micro-mobility transport offering, which consumes less road space, is more energy-and-cost-efficient and is specifically designed for short, single-user trips, could go a long way towards improving the flow of downtown movement, especially those still heavily reliant on car use. In university zones, this potential capture timeframe is stretched over a longer period of time (from morning to the end of lunchtime).

2 Internal trips have an average share of a quarter of all trips during lunchtime.

Towards a new mobility landscape

The mobility ecosystem is gradually expanding into a more diversified portfolio: the personal and collective mobility spheres are exploring shared, electric, automated, on-demand, micro- and integrated solutions to fit conflicting needs in a fast urbanizing world. Trends discussed within the book point to the growing adoption of American cities of new alternative mobility options.

The progressive cities framework

Within this study, the progressive (versus non- progressive) cities framework was used as a way

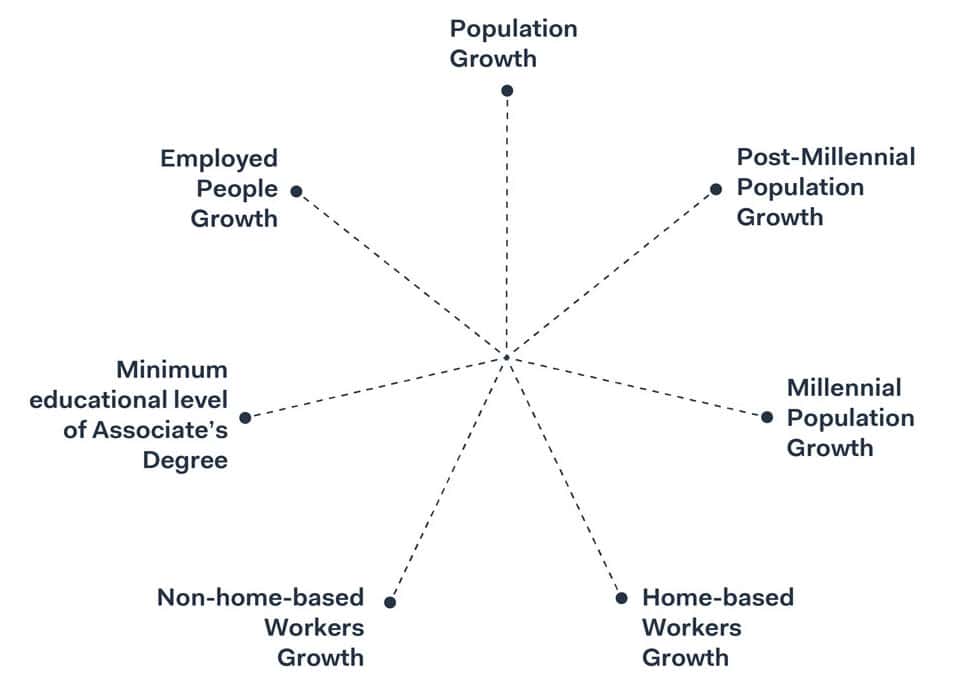

to read mobility trends. In progressive cities, which were the focus of this book, a number of co-existing socio-demographic, economic and behavioral conditions were used as parameters feeding into a ‘progressiveness index’. These parameters were designed with the aim to highlight cities showing healthy economic growth trends and a significant representative share of progressive behavioral outliers (millennials, in this case). A select number of cities, which performed well on these scales were tested for a number of progressive mobility trends, as signals of a potential model mobility landscape to replicate across the country.